The rapid rise of social media made it easier for people to share updates and developments in their lives – often including starting a family and posting about childhood milestones. In some ways, social media platforms have become modern-day “baby books.”

A trend has emerged – “sharenting” – which features parents posting about their children online. Some children even have images on social media before they’re born, in the form of ultrasound photos.

But when it comes to sharing content with children on social media, even going as far as turning them into props for sponsored posts and brand partnerships, just because it’s legal doesn’t mean it’s ethical.

Parent influencers are increasingly turning their children into influencers in their own right and monetizing their work. Illinois is now the first state to pass laws to protect child influencers, potentially sparking a trend that other states will follow.

When Sharenting Becomes a Prop

Children have been part of the social media space since the start, but with the rise of influencer marketing, there are growing issues around the lines between sharing personal lives, which often includes family, and monetizing children.

Older social media users have been fortunate to miss out on having every detail of their childhood documented on social media. Now, parents are sharing everything from ultrasound photos to first steps to embarrassing and intimate moments, such as diaper changes or baths.

There are growing concerns about the lack of privacy given to children when their parents engage in sharenting. These children often end up as influencers, either through their own content or within content from a parent influencer – raising questions about privacy and compensation.

For example, influencer Brittany Dawn, a fitness influencer who shifted to more religion-based content, faced a lot of scrutiny for monetizing her foster child on social media. Though she blurred out images in her photos, a stipulation decreed by the U.S. Children’s Bureau for foster parents in their social media rules, she was able to capitalize on her foster child by using affiliate links to promote baby products and earn a commission.[1]

Source: Instagram

Also, the YouTube family influencer Myka Stauffer shared details about her children and discussed her experience of adopting a baby boy from China. She featured him in a lot of her content, leading to criticism from some followers – which grew when she made the decision to put him up for adoption.[2]

Source: YouTube

Showcasing children is a niche. Sometimes, an influencer in the travel or fashion space makes a shift to a parent influencer once they start a family. They take their dedicated following on journey with them through the big milestones, including pregnancy, birth, first steps, the first day of school, and so on.

The problem is that children can’t consent to their appearance on social media. When non-influencers engage in these behaviors, it’s mostly for friends and family. When influencers do it, they’re sharing with tens of thousands, or even millions, of virtual strangers.

Children don’t understand the true breadth of the internet and the potential long-term ramifications of being broadcast to a vast audience of followers from all over the world. The internet is forever, and there’s no telling how those “cute” videos may impact a child’s life when it comes time for college or a job.

The Child Labor Law in Illinois

There’s nothing to stop parents from posting pictures and videos featuring their kids on social media, until now. Illinois recently passed a law that establishes safeguards for minors who are featured in online videos and guidelines for compensation.

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill on August 11, 2023, to amend the state’s Child Labor Law and allow teenagers over the age of 18 to take legal action against their parents if they were featured in monetized social media videos and not properly compensated.[3] This is similar to the rules that protect child actors and performers.

Starting July 1, 2024, parents in Illinois will be required to put aside 50% of earnings for content into a blocked trust fund for the child based on the percentage of time they’re featured in the video. This only applies to scenarios where the child appears on the screen for more than 30% of the video in a 12-month period, however.

Updating the Coogan Act

Though Illinois is the only state that’s put a law into place to address the growing controversy around children on social media, there is a law on the books to protect the rights of child performers – the Coogan Act in California.

The state passed the Coogan Act, also known as the California Child Actor’s Bill, in 1939.[4] It was named for the former child actor Jackie Coogan, who’s often regarded as America’s first child actor.

Coogan became famous as Charlie Chaplin’s adopted son in the 1921 film “The Kid,” but once he reached adulthood, he discovered that his parents squandered his $4 million in earnings. That would amount to tens of millions today. He was ultimately able to reclaim only a small portion of his total earnings.

The Coogan Act protects children who have been hired as an actor, actress, dancer, musician, comedian, singer, or other performer or entertainer and safeguards their compensation until they reach adulthood. Several other states have similar legislation in place, but none of these laws have been updated for the digital age.

There’s a growing movement to update the Coogan Act and similar laws to include the children of parent influencers, or better yet, create a law on the federal level. Currently, it only protects children in traditional entertainment.

In addition, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which protects children from excessive labor, has not been updated to apply to child influencers or the children who are regularly featured on their parents’ feeds.

Protecting Child Performers in the Digital Age

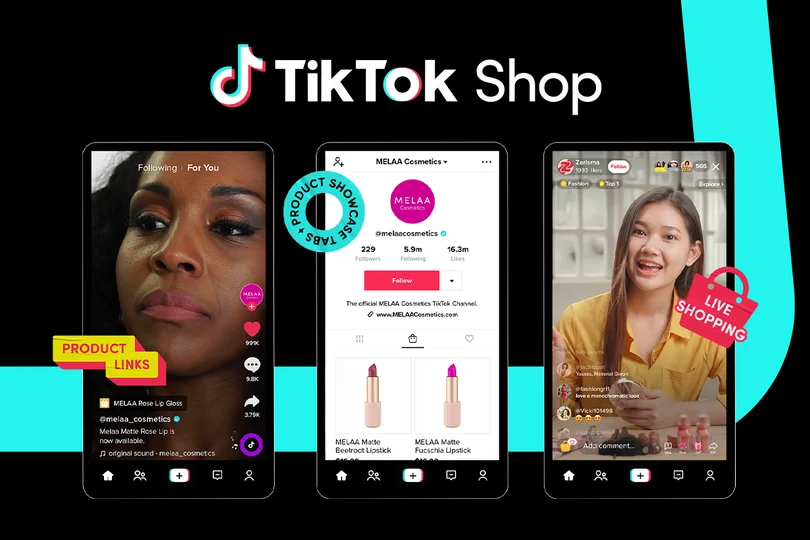

Illinois’ Child Labor Law is a step in the right direction, but in the rapidly evolving digital landscape, children are often shared on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok to huge audiences. This is a new frontier with little insight into the long-term effects of these practices on children and the issues surrounding privacy, safety, and compensation, highlighting the need for updates to the new definition of child labor in the digital age.

Sources:

[1] https://www.insider.com/christian-influencer-brittany-dawn-criticism-foster-parent-journey-2022-12

[2] https://www.thecut.com/2020/08/youtube-myka-james-stauffer-huxley-adoption.html

[3] https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/fulltext.asp?Name=103-0556

[4] https://www.sagaftra.org/membership-benefits/young-performers/coogan-law